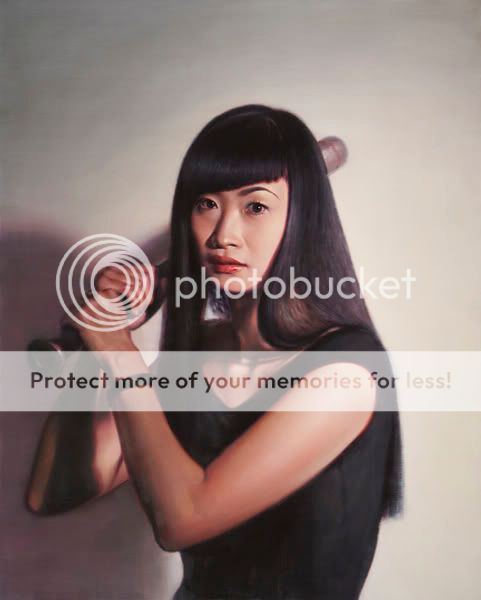

Winky, San Francisco Seals, 2010, Stacey Carter

Winky, San Francisco Seals, 2010, Stacey Carter

I’m standing next to Tom O’Doul, 67, who looks so much like his famous cousin Lefty O’Doul it’s uncanny, and as we view a painting of a bat boy for the team Tom once knew, he says it’s fairly accurate. Never a bat boy himself, though he got to go in the dugout during games, Tom explains a subtly the artist captured, how San Francisco Seals bat boys received a blue cap with SEALS in white block letters, while players got caps with SF lettering.

It’s the sort of attention to detail that sometimes gets neglected in other works. Art and baseball don’t always have the smoothest conflux, as Lefty O’Doul could attest from his time trying to teach Gary Cooper how to properly swing for Pride of the Yankees or the makers of Field of Dreams might cop to, since they had Shoeless Joe Jackson bat right-handed since he hit from the left but Ray Liotta could not. Still, many of the works in the 13th annual Art of Baseball exhibit at the George Krevsky Gallery in San Francisco accurately reflected the game.

I attended the exhibit Thursday evening with Tom O’Doul and other members of the Society for American Baseball Research, which I recently joined. Coincidentally, the gallery is three blocks down Geary Street from Lefty O’Doul’s bar and restaurant.

I’m generally not much of a museum guy. While some people spend hours looking at a painting, I could probably do the Louvre in under a half hour. Heck, I even breezed through the National Baseball Hall of Fame when I was there in 1997. So I don’t have any sophisticated artistic expertise to offer here, besides to say that aesthetically, I found the show pleasing.

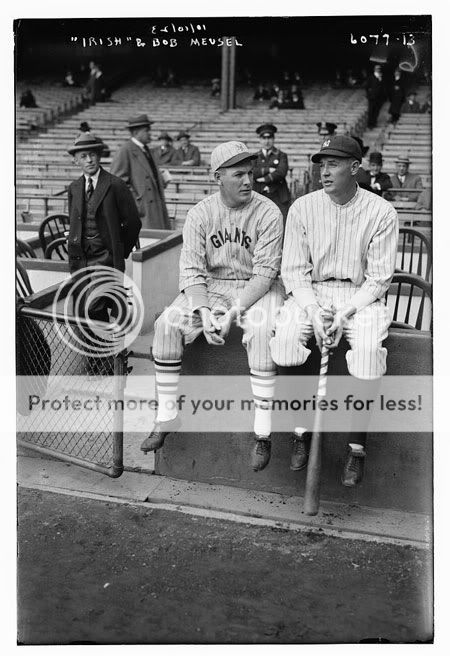

The works varied in style, though some of my favorites had a lifelike quality to them. Arthur K. Miller contributed paintings of Mickey Mantle, Juan Marichal, Satchel Paige and this one of Tim Lincecum:

Tim Lincecum, Arthur K. Miller

Tim Lincecum, Arthur K. Miller

I enjoyed talking baseball with the various people in attendance, including gallery owner George Krevsky, who said he played baseball for Penn State. I pride myself on my baseball library, and Krevsky has one that could rival it in the office that connects with the main room of his gallery. Along with classics I’ve read like The Boys of Summer and Baseball’s Great Experiment, I noticed copies of three books by Jim Bouton, one of my favorites. Krevsky said Bouton used to play handball with his father, who was nationally ranked and that in years past he’s wanted to get Bouton to the show.

This year, Krevsky featured a reading and signing by another author, Jeff Gillenkirk, who’s written for The New York Times, The Washington Post and Mother Jones magazine and whose latest book, Home, Away debuts this month (Gillenkirk said a glitch on Amazon says it can’t be purchased there until September but that it’s available on his publisher’s Web site.) The book is about a ballplayer who leaves the big leagues to be closer to his son, and Gillenkirk read an excerpt where the 39-year-old protagonist winds up in independent league ball at $65 a game.

All in all, it was an enjoyable night and probably the last time I’ll go to an art show for a long time unless I meet a girl or the San Francisco Giants invite me to a gallery opening. In a perfect world, both could happen.

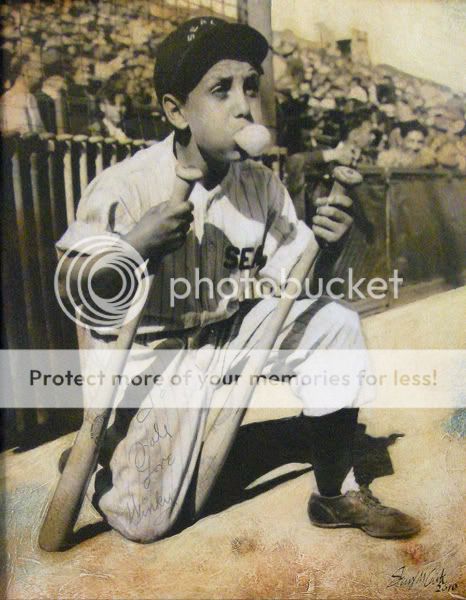

I’ll close with this last work by Valentin Popov, a Ukrainian-born artist Krevsky said he’s admired for years but had never painted baseball before and “didn’t know baseball from a pineapple.” I would be interested to see what other baseball works Popov can produce.