As regular readers might recall, I spent an hour on the phone in April 2020 with Maury Wills for Sports Illustrated. As often happens with long interviews and subsequent 1,500-word articles, a lot of good stuff wound up on the cutting room floor when I went to write. Among this: Much of what Wills told me about barnstorming with a team, Jackie Robinson’s All Stars in the fall of 1953.

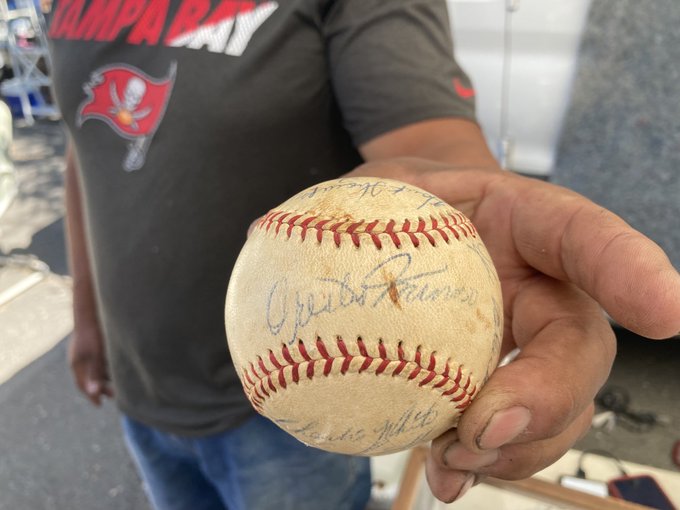

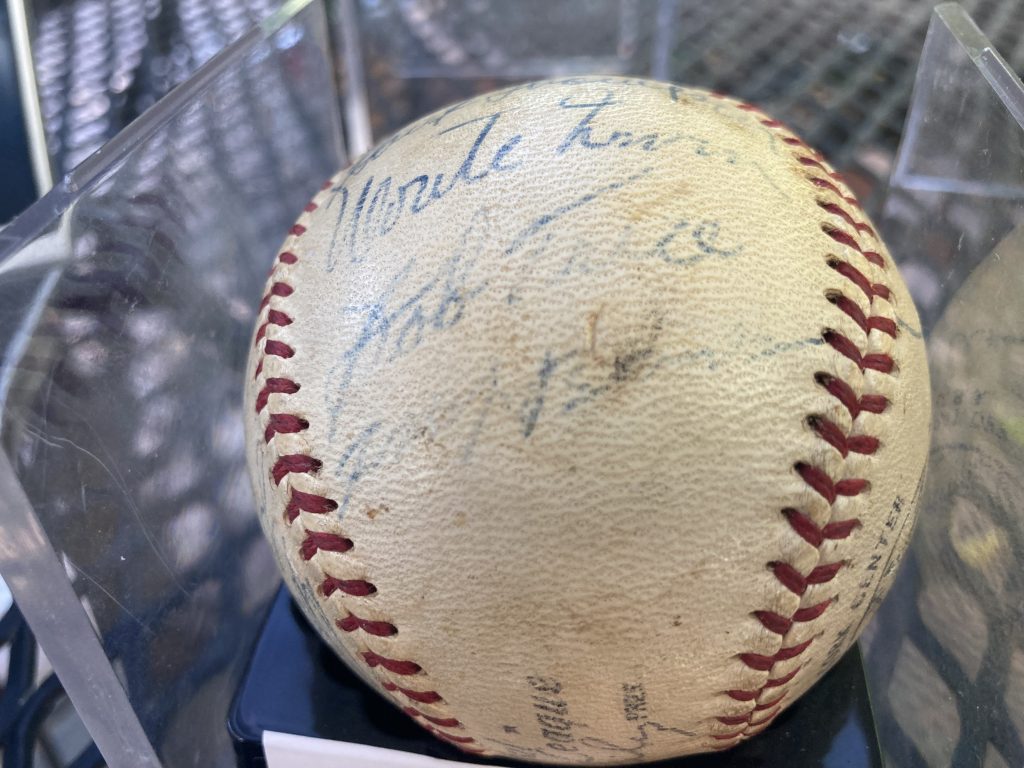

I was reminded of this again this week in finding an autographed baseball at an antique fair from another barnstorming team, Roy Campanella’s All Stars of 1955. In researching the origins of this ball, I learned that Black barnstorming teams were much more common than I thought and it’s motivating me to share a little more of what Wills told me.

In my piece for SI, I talked about how Wills idolized Robinson growing up in Washington D.C., how he was written of as a pitcher (which he’d done a little in the minors) on the barnstorming tour, and how he’d gotten $300 a month for the tour. “I would have barnstormed with him for nothing, but they didn’t know that,” Wills said of Robinson, as I noted for SI.

There’s definitely more to the barnstorming trip than what could fit at the time in my SI article, which went through Wills’ entire career in the majors and minors.

Wills joined the barnstorming club a few years into his professional career with the Dodgers, having played only in the low minors to this point. While Wills would eventually go on to become a star shortstop in Los Angeles, leading the National League in steals six consecutive seasons from 1960 through 1965, he was still years off of even making the majors when he joined Robinson’s team.

Turning 21 in October 1953, Wills was part of an integrated barnstorming team with white players of note like Gil Hodges, Al Rosen, and Ralph Branca and legends of Black baseball such as Luke Easter. “That was the thrill of my life at the time,” Wills said.

Not having a roster in front of me at the time I interviewed Wills, I didn’t ask what it was like for him to play on the barnstorming team with Hodges, Rosen, or Branca. I did ask Wills what Robinson was like in person, with Wills telling me, “He was very aloof. But a nice man. Aloof. He didn’t get involved with any controversy or anything like that.”

My favorite thing that I left on the cutting room floor concerned Wills’ interactions with Easter, something of a tragic figure from baseball history for multiple reasons. First, Easter was barred from the majors until well past his 30th birthday due to the game’s color barrier. Easter would die tragically as well, fatally shot in a payroll robbery in 1979 according to his SABR bio.

By the time Wills got to know him on the barnstorming tour, Easter was a 38-year-old first baseman on the downslope of his brief big-league career after a few years of stardom with Cleveland Indians. “Luke had his own chauffeur with a big Cadillac,” Wills said. “I was a minor leaguer from the Dodgers. We rode on the bus with the opposing team, the Indianapolis Clowns from the old Negro Leagues.”

Stories of Negro League accommodations can be notorious. It was no different with this bus. “The bus was like, oh man, it was bad. But everything was in that bus,” Wills said. “It was like a gymnasium.”

So Wills decided he would ride in Easter’s Cadillac, befriending him and becoming his driver. “That was quite an experience, driving all through the South… and here I was driving Luke Easter around,” Wills told me. “He’s sleeping in the back seat and I’m on that freeway or highway, going through the South at night. Big curves and everything and big trucks on the road, headlights hitting you right in the face, going around curves. But it turned out alright.”

For Wills, it was a small taste of the big life, with several more seasons beckoning in the minors before he could find it for himself.