In a town just north of San Francisco, I watched as Sandy Koufax got a round of applause.

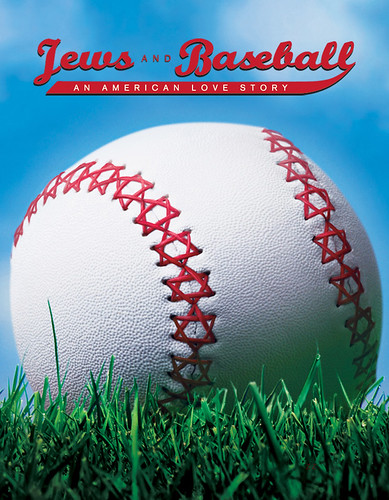

No, I wasn’t in a room full of Dodger fans, a nightmare for any longtime Giants supporter who knows only too well how Koufax forged the best years of his Hall of Fame career keeping San Francisco mostly out of the World Series. I was at a screening in Marin County on Sunday of Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story, a film about Jewish ballplayers from the 19th century to present day. For some reason, of the couple dozen players shown onscreen, Koufax got the loudest response. It happened right as my date was getting up to use the restroom, so I told her people were cheering for her, though of course, something else was at work here.

Greats like Koufax, Hank Greenberg, and some of the other Jewish ballplayers depicted in the film seemed to attract followings which transcended their teams and have inspired tributes even decades after retirement. Some of it is probably faith-related, and I noticed at least one person in a yarmulke. I suppose others, like myself, merely try to honor greatness in all its forms and can’t help but be touched by the grace of a Koufax or a Greenberg, who each stayed true to their faith and ideals and persevered through adversity. Their experience brings out the best in sports, no matter their team.

With that said, the film went well beyond the obvious. Last November, I re-watched The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg, a nice 1999 documentary about the Detroit Tigers Hall of Famer, but one that doesn’t explore much deeper than him. Jews and Baseball, on the other hand, features players as far back as the 1860s. There are of course the obligatory mentions of names that seemingly arise anytime there’s a discussion of Jewish ballplayers, stars like Koufax, Greenberg, and, in recent years, Shawn Green. But over the 91-minute running time, we learn of such forgotten heroes and would-be greats as Lip Pike, Andy Cohen and Mose Solomon who was touted as “The Rabbi of Swat,” when he joined the New York Giants in 1923. I enjoyed and was somewhat surprised at the history lesson.

Some of it may be a credit to screenwriter Ira Berkow, a retired sports columnist for the New York Times, who penned an engrossing biography of sportswriter Red Smith in my personal collection. The film, which screened as part of the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival, was directed by Peter Miller, a veteran of the documentary circuit. Miller’s biography shows no baseball-related works, though he has producing credits on three non-sports projects by Ken Burns, who directed the Baseball mini-series that aired on PBS in 1994. Whatever the methodology, the result is something better than a mere cobbling of Koufax, Greenberg and Green anecdotes, which could have been an easy out for this project. This also was a great movie to see with a non-baseball fan.

At least one former ballplayer was in attendance Sunday, a San Francisco native named Ed Mayer who pitched for the Cubs in 1957 and 1958. Mayer was passing out replicas of this card to moviegoers on Sunday:

I chatted with Mayer after the film, and he told a story that bears repeating here. The film drew parallels between black and Jewish ballplayers, who each faced stereotypes from opposing players and fans. While Mayer said that in the minor leagues he endured anti-Semitic taunts from a fan in Minneapolis and was denied entry to a members-only club in Phoenix, he said blacks had it tougher.

Mayer recalled a minor league bus trip in Georgia with future 22-game winner Earl Wilson. At a service station, Wilson attempted to buy a Coke and had a gun pulled on him by the station owner. Mayer wound up buying the coke for Wilson from the owner and noted to me, “If he knew I was a Jew, he would’ve shot me too.”

It’s way past time to get beyond race, religion and the other things that keep us divided, hating and quarreling with each other, and instead start to focus on the things we share in common. If we can’t bring ourselves to help others out in this life, at least we should try doing them no harm.

The men highlighted in the film should always be remembered as ballplayers first

and anything else second. They made it to the major leagues because they were

good enough to get there, not because of their religion but perhaps in spite of it.

If their religion made them heroes for some so be it. The fact is players like

Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax were heroes to many of all faiths because

of their deeds on the field and that’s the way it should be.

I think that Hank and Vinnie are right and we need that point of view now more than ever. I’d only add that in my home going back years ago, it meant something for me and a million kids like me to see left-handed pitching, Jewish, Brooklyn-born, Sandy Koufax go out there and strive for excellence. When you grow up and don’t see anyone out there like you and suddenly do, it is inspiring– just as it was for blacks with Jackie and Joe Louis. That type of regard has nothing to do with racism, rather a form of identifying and being inspired by someone that comes from the same origins. It never made me feel better than any other race or culture or religion, it was just nice to see him out there.

Personally, my life-long heroes cross the color and cultural line, Roberto Clemente and Martin Luther King to name the two who I carried the deepest in my heart as a child and still do today.

Was Roberto Clemente also Jewish?