There once was an iconic sports star who transformed his game, was its first marketing icon and was so renowned and beloved he was known by a single name.

Generations before Tiger, there was the Babe.

Over the past several months, I have been struck by the similarities between embattled golfer Tiger Woods and the greatest ballplayer of all-time, Babe Ruth. For one thing, were Ruth still alive, he could probably relate to Woods’ well-chronicled marital woes. In the Twenties, Ruth went to greater excesses.

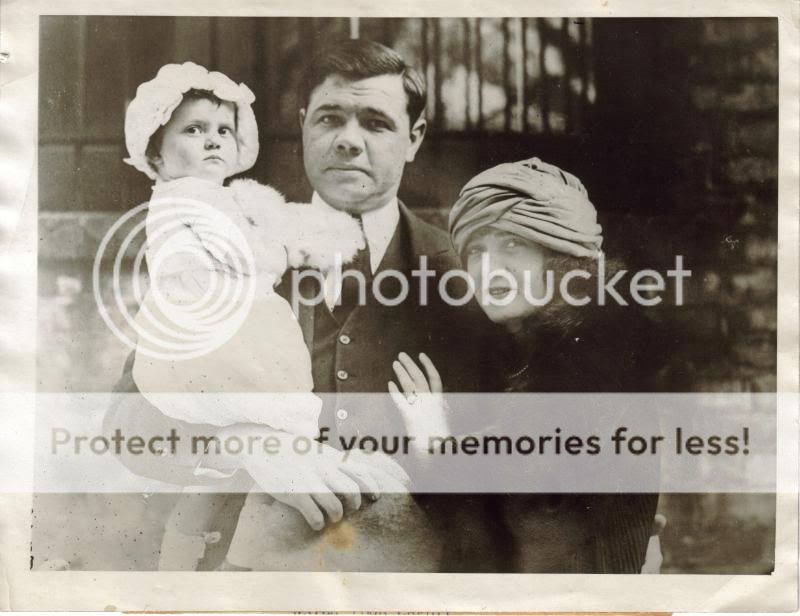

The above picture is of Ruth with his wife Helen and their adopted daughter in 1923. The marriage didn’t last. As chronicled in Ken Burns’ Baseball, Ruth was “a favored customer in whorehouses all across the country” and collapsed in 1925 with what was privately speculated by sportswriters to be venereal disease (publicly they wrote it was the result of too many sodas and hot dogs, and one called it the “bellyache heard round the world.”) After Helen Ruth suffered a nervous breakdown, the couple agreed to separate. She died four years later in a house fire, living with another man under an assumed name.

In a sense, Woods is lucky. I’ve written before that I think he’ll be fine, and while I don’t know if I believe that as strongly anymore, his estranged wife Elin appears to be doing well, while she takes college classes in Florida and contemplates whether or not to file for divorce in the wake of serial infidelity.

With that said, the parallels between Ruth and Woods extend far beyond philandering. A good Orlando Sentinel article from April delved into this somewhat, though there was stuff it missed. I’ll list some of the major similarities chronologically:

- Woods is of mixed race, and Ruth was rumored to have black ancestry, which was part, I would venture, of what helped give them folkloric status among much of America.

- Both had challenging relationships with distant, demanding fathers. A new book, Tiger: The Real Story recounts Woods’ mercurial bond with his late dad, Earl. Ruth had a lookalike bartender father who placed him in reform school at a young age.

- Each man got an early start professionally. Ruth debuted in the majors at 19, while Woods played in his first Masters at that age.

- Both were light years beyond anyone they played against.

- They each were the first heavily-marketed stars of their sports. Ruth hawked everything from Wheaties to cigarettes, while decades later, Woods became the face of Nike.

- Both took their sports to different levels, Ruth by rescuing the game in the wake of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, Woods by bringing in a new, youthful breed of golf fans.

- The media chastised each man, leading them to publicly promise change. For Ruth, those promises didn’t last more than a couple of years. It will be interesting to see if Woods fares better.

Players like Ruth and Woods are rare, icons with a combination of skill and larger-than-life marketing status. Shaquille O’Neal has it, maybe Michael Jordan, maybe Lance Armstrong. It’s a tough mantle to attain. It’s tougher to live up to.