On Friday, I said I’d highlight a seven-part series today that the Associated Press offered in 1954 with instructions on how to play baseball from Hall of Fame shortstop Honus Wagner. When I went to research this piece, I realized I’d goofed. In 1954, AP Newsfeatures produced a seven-part series of former big league stars offering playing tips. It’s the kind of thing that would be great to see today, if only anyone still read newspapers.

With the help of newspapers.com, I tracked down all seven parts of this series. They’re highlighted and linked to as follows:

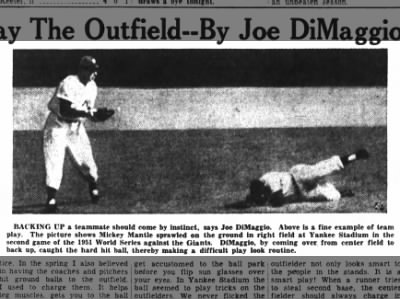

Part I: “How to play the outfield,” by Joe DiMaggio

The caption for the photo above begins with a quote from DiMaggio saying, “Backing up a teammate should come by instinct.” It’s a curious choice of photo. It shows Mickey Mantle blowing out his ACL in the second game of the 1951 World Series, after the Yankee Clipper called for a ball Mantle was running down in right field. The caption praises DiMaggio for “making a difficult play look routine,” which he did often during his Hall of Fame career. But it was also the first of many serious injuries for Mantle.

DiMaggio noted in the article:

Had that ball gone through us I would have had to chase it since it was coming toward right center. It might have gone for two or three bases, and we might not have beaten the Giants by 3-1 that day.

Part II: “How to play third base,” by Pie Traynor

It’s odd to think that at the time this series ran, Traynor was considered by many to be the greatest third baseman in baseball history.

Mike Schmidt , Brooks Robinson, George Brett and others have long since eclipsed Traynor in the running for this honor. Sabermetrics also shows that Traynor might be one of the more, if not most overrated all-time greats. His 36.2 career Wins Above Replacement ranked 13th among third basemen up to 1954. But that stat was a long way off back then and Traynor’s .320 lifetime batting average was tops of any living third baseman in 1954. Traynor still has the third-best lifetime batting average among third basemen after Wade Boggs and John McGraw.

Traynor’s article for the second part of this series focused on the defensive aspects of his position. Aside from various pointers, Traynor wrote of a play he’d devised. He noted:

When the ball was hit to me at third base and with a runner on third I would fire the ball into the plate to get the man going home with one out or less.

The moment I threw the ball I would run as fast as I could and the moment the runner held up, the catcher would return the ball to me. It was easy to tag the runner. I would be standing next to him. But wait! As I tagged the runner, I’d be getting set to make a throw to first base to get the batter. And many times we’d get the batter because he had made the turn of first base toward second.

Part III: “Shortstop is key position– says Honus Wagner”

1954 was a good year for Honus Wagner. All throughout the year, the Pittsburgh Pirates took donations from fans to build a statue of their legend beside Forbes Field. Dwight Eisenhower, among others, called Wagner to wish him a happy 80th birthday on February 24. A few months later, AP Newsfeatures sports editor Frank Eck interviewed Wagner for the third part of this series. It’s the only installment, incidentally, where a player is not given byline credit.

Wagner, the eighth-oldest living Hall of Famer at the time, offered a number of gems in the piece, including:

I stayed at shortstop until the ball was hit or pitched out. I learned that from Hughie Jennings back in 1897 when I was playing right field for the Louisville Colonels in the National League. Jennings hit .397 for Baltimore in 1896 and when I came up as a 23-year-old rookie, I thought I’d see how Jennings did it. Jennings was a shortstop but how he could cover second base! He could take the throw while on the run.

Part IV: “How to play second base,” by Rogers Hornsby

It’s funny, I never think of Rogers Hornsby for his defensive contributions. I think of the lifetime .358 batting average or the .402 clip he managed from 1921-25 or the two Triple Crowns. Even with sabermetrics that mitigate for the superb offensive era and ballparks he played in, Hornsby’s batting feats are still astonishing. His 175 OPS+ is fifth best in baseball history and his 173 wRC+ is tied for third.

I’ve traditionally thought of Hornsby as a second baseman only in the respect that’s it where I’d tolerate playing him in exchange for having his bat in the lineup for my all-time dream team. But he knew enough about the position to write the fourth installment in this series. Hornsby wrote:

Some fellows say the second baseman should face partially toward first base when fielding ground balls. I disagree. A second baseman, or any fielder for that matter, definitely must get in front of all ground balls. Never play a ball off your side. Try to play the ball with both hands. There is too much of this one-handed stuff today. Use one hand only when forced to.

The article also included a quote from legendary New York Yankees manager Casey Stengel, who’d faced Hornsby as a player. Stengel said, “I never saw any other second baseman throw sidearm and get the speed on the ball that Hornsby did.”

Part V: “Bill Terry offers some tips on how to play initial sack,” by Bill Terry

Terry’s another player I know chiefly for his bat, the last man to hit .400 in the National League thanks to his .401 season in 1930. Sabermetrics suggests he was a decent fielder as well, with Terry saving 73 defensive runs during his career, 11th-best among first basemen all-time. Terry wrote in the fifth installment of this series:

I see all sorts of players, men who have come up as catchers, outfielders and infielders at other spots put on first base. It seems the popular trend is that if a man can’t play any place else, or is beaten out of his job they put him at first.

I have never considered it that simple. A good first baseman can save a team a lot of base hits by going after the close ones. He should stretch on every play, automatically. A good first baseman can save a team a lot of errors by fielding the bad ones.

Part VI: “Easy delivery aids control,” by Carl Hubbell

Aside from striking out five consecutive future Hall of Famers in the 1934 All Star Game, Hubbell was perhaps most famous for his screwball pitch. Interestingly, in the sixth installment of this series, Hubbell cautioned aspiring hurlers against throwing too many different pitches or getting excessively creative.

Hubbell wrote:

Tricky deliveries may succeed on the sandlots but as a pitcher moves into faster company he will find that the pitch that overpowers a good hitter will be his best weapon.

It’s interesting, by the way, to see Hubbell as an authority on power pitching. His 1,677 strikeouts rank 137th in baseball history as of this writing. In 1954, though, they were 26th-most ever and 15th-most by any pitcher since 1901. The times, how they’ve changed.

Part VII: “Good arm, quick reflexes make top catcher,” by Gus Mancuso

For the final installment of this series, the AP turned to Mancuso, the only player of the seven not in the Hall of Fame today. In fact, everyone else but DiMaggio– whose 1951 retirement and 1955 induction helped inspire the five-year waiting period for eligibility– had already been voted in by the time this series.

There weren’t a ton of legendary former catchers to approach in 1954 [though with some foresight, then-active catchers like Yogi Berra or Roy Campanella might have made great choices.] Bill Dickey and Mickey Cochrane were the only two living catchers who’d already been enshrined in 1954. Presumably, future honorees like Ray Schalk, Ernie Lombardi and Gabby Hartnett weren’t available.

Instead, readers got Mancuso, a 17-year National League veteran who made two All Star teams and twice finished in the top ten for MVP voting. Perhaps Mancuso had something to offer as an instructor as well, as he managed in the Texas League from 1946 through 1949.

Among Mancuso’s instructions in this piece he wrote:

The catcher must get his pitchers to respect his judgment because when a pitcher gets in a jam his catcher often can help him as much, and maybe more, than his manager or coach. The catcher is definitely the quarterback of his team.

_________________________

I wonder who might figure into a similar series today?