With infection numbers from the COVID-19 pandemic finally beginning to wane in America, life is starting to get back to normal. One facet of this has been the resumption of the monthly Antique Faire in the city I live, Sacramento. The latest one happened yesterday and led me to a piece of baseball history I’ve spent the last 24 hours swept up in.

For those unacquainted, which is likely most people reading, this fair happens on the second Sunday of each month. Until recent times, it was held under a freeway at the south end of Sacramento’s central city, though construction recently forced it to relocate to the former home of the Sacramento Kings, Sleep Train Arena. At each site, the same thing happens: Vendors set up informal, outdoor booths and members of the public pay a $3 fee at the main entrance to browse.

Initially, my wife Kate and I had gone to the fair yesterday to maybe find a few items for our house. We bought our first place about nine months ago and it still feels like a work in progress. But after a short time at the fair, Kate and I got separated and I found myself at a booth with a few items of sports memorabilia.

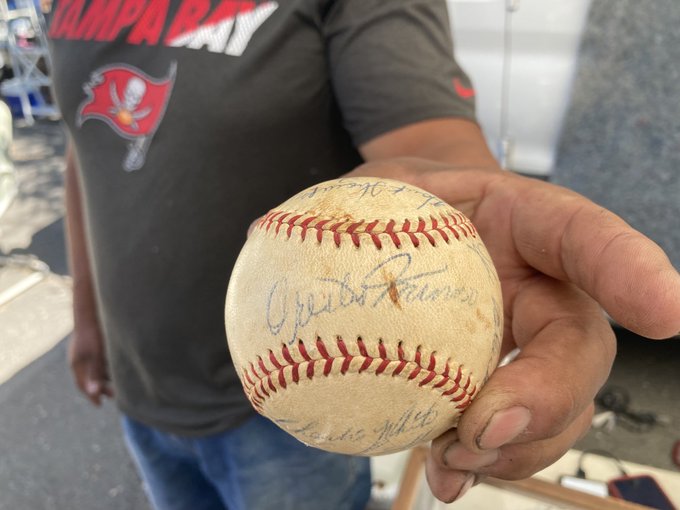

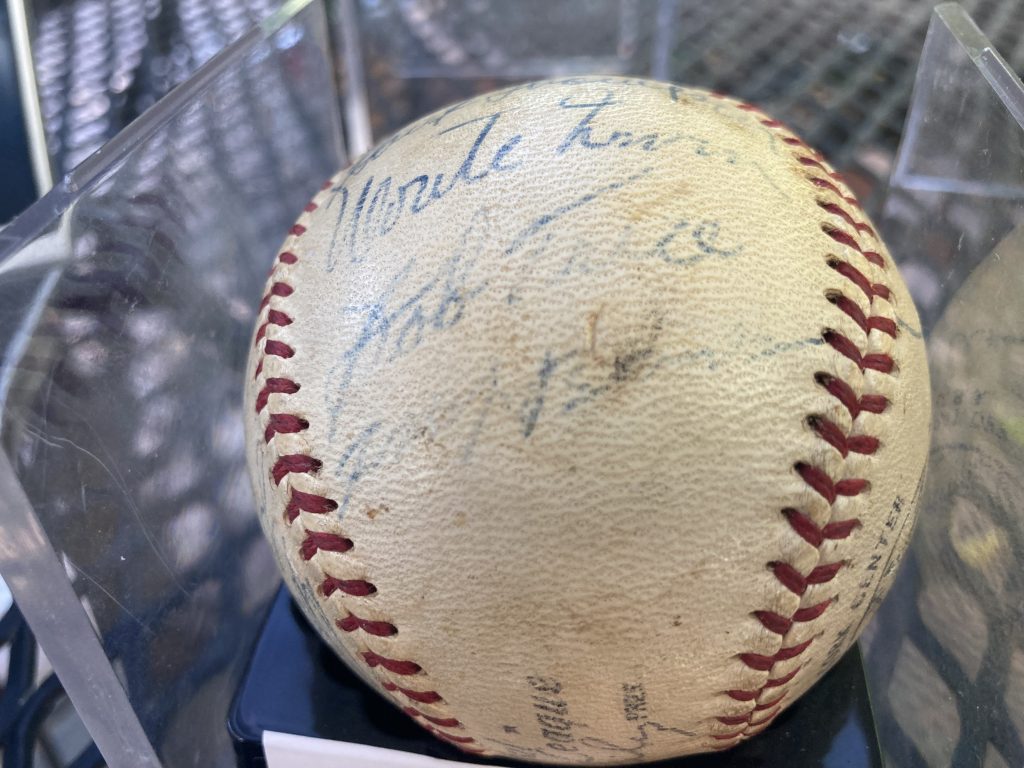

I suppose some people collect sports memorabilia voraciously, either to resell or keep in private collections. I’m not this kind of person. But as someone who loves researching and writing about baseball history, I was intrigued the second I saw a dirty autographed baseball in a case at this booth. I asked if I could hold the ball and saw Minnie Minoso’s birth name, Orestes. Turning the ball over, I was stunned to quickly recognize Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, Joe Black, and Hank Thompson as well.

The seller mentioned that he wanted $300 for the ball, which was more than I wanted to pay. He lowered the price to $200, which seemed very reasonable to me, but still a lot. As I mentioned, I don’t buy a lot of memorabilia. As a full-time freelance writer, I’d rather interview an old ballplayer free of charge (and maybe sell an article out of it) than plunk down hard-fought earnings for something that’ll sit on one of my shelves. I just don’t see the point.

But I also had the feeling that this was an item of special historical significance, something I shouldn’t pass up. I tweeted out the photo above of the seller holding the ball and the immediate response from Twitter was enough that I found an ATM on-site, withdrew $200, and bought myself a ball.

In just over 24 hours since, my task has morphed into trying to figure out where this ball came from. Aside from the six players I listed above, I have identified five others: Jim Gilliam, Bob Trice, Charlie White, Jim Pendleton, and Al Smith. I’m reasonably certain Gene Baker is on the ball as well. One more signature, at bottom below, is too hard to read, though there’s a chance it’s Roy Campanella, Dave Hoskins, or Brooks Lawrence.

The reason I say this is that the 11 players I’ve identified so far and the additional one I’m reasonably certain on all played for Roy Campanella’s All Stars, a 15-player barnstorming team from 1955. (I found a full roster here.) Like Campanella, each man had played in both the Negro Leagues and either the National League or American League. In the time before free agency and television revenue helped increase baseball salaries exponentially, every one of these players could have used an offseason side hustle. Barnstorming was a common way it happened through the 1950s.

In all, the ball has 13 signatures, meaning that two players from the team more than likely didn’t sign it. My gut is that Campy passed on it and that the final signature might be from Hoskins or Lawrence. But it also could have been a random clubhouse person or coach, I’m really not sure. I’m sharing the signature in hopes that someone might know better than me.

I’m curious where the ball came from. The seller told me he found it in a box. The ball doesn’t have a certificate of authenticity and it’s possible some sick soul sat down and devised a very convincing forgery. Still, it seems far too specific to be made up for me and I think a forgery would have a clearly legible signature from Campanella and all 14 other players from the team. The fact that all 13 signatures on the ball are in the same ink color tells me that someone more than likely took a pen and the ball and got signatures from as many players as possible.

After I’ve had a little more time with the ball, I intend to donate it to the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City. It’s the kind of item that belongs in a museum and if spending $200 on an impulse purchase at an antique fair helps me do my part, it will have been well worth it.

This is fantastic Graham. Congrats on preserving this little bit of history.

Thanks, Mark!

Great story and great find. Very generous of you to donate to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, where it will be appreciated and enjoyed in that great forum. The stamp on the ball may also help narrow down the date the ball was signed (or at least when the ball was in use). Wonderful item.

Thanks, Danne. I figure the very close roster match and the similarities in pen ink color and signature size make me reasonably certain it’s from the Campanella team.

Aside from that, two other looser clues on the ball’s era are that it’s a National League ball from when Warren Giles was president, meaning the ball came out sometime between 1951 and 1969. Hank Thompson also died in 1969, meaning at the absolute latest, someone started getting signatures on the ball that year of players who’d all been on the team.

That said, given the amount of work involved to gather signatures from the team retroactively and individually (unless there was a reunion sometime prior to Thompson’s death), it seems more likely to me that someone got a ball signed by most of the team when it was in action in 1955. It just seems like the easiest explanation for why this ball exists.

This is one of the best things I have stumbled across in a long time. By chance, have you submitted it for signature verification? PSA I believe has this service. Seriously, I am dying to know how this story unfolded. That is one HELL of a find.