It ranks as one of the more enduring mysteries in baseball history. The inaugural 1901 season of the American League also marked the debut in the majors of 29-year-old Irv Waldron. While not a star, the 5’5″, 155-pound outfielder hit .311 between the old Milwaukee Brewers [who became the St. Louis Browns in 1902] and Washington Senators, with a 106 OPS+ for the year. And that was it for Waldron. While he played another nine seasons for various minor league teams, he never returned to the majors after 1901.

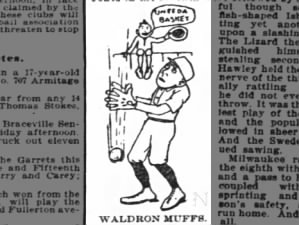

I’ve written about one-season MLB careers before. What makes Waldron’s unusual is that it didn’t end for the typical reasons– injury or lack of ability. Granted, he finished third in errors by an outfielder, his defense suspect enough to inspire a derisive Chicago Inter Ocean cartoon, at right. But Waldron likely could have gotten more work playing in the majors. Late in the 1901 season, the Boston Beaneaters of the National League expressed interest in signing him for their depleted outfield. Tangentially, one of the Beaneaters stars of 1901 figured in where Waldron played in 1902. More on that in a moment.

I’ve written about one-season MLB careers before. What makes Waldron’s unusual is that it didn’t end for the typical reasons– injury or lack of ability. Granted, he finished third in errors by an outfielder, his defense suspect enough to inspire a derisive Chicago Inter Ocean cartoon, at right. But Waldron likely could have gotten more work playing in the majors. Late in the 1901 season, the Boston Beaneaters of the National League expressed interest in signing him for their depleted outfield. Tangentially, one of the Beaneaters stars of 1901 figured in where Waldron played in 1902. More on that in a moment.

To my knowledge, no one’s ever definitively stated the reason for Waldron’s exit from the American League. Seemingly, no one thought to interview him before his death in 1944, with his obituary making no mention of why he left the majors. Waldron has no SABR biography and scant details accompany his stats at Baseball-Reference.com. What’s been written is largely speculative, like this book noting, “His reputation for bone-headed playing must have stayed with him.” The Ultimate Baseball Book classes Waldron “among the most mysterious figures to wear major league uniforms.”

Waldron’s departure was mysterious even at the time. MLB historian and veteran baseball author John Thorn sent me an excerpt from a Febuary 1, 1902 article in Sporting Life that asked of new Washington manager Tom Loftus:

Why has he permitted Sam Dungan and Irving Waldron to slip away and fall into the minor leagues? They hit way over .300 last year why were they not good enough for 1902? The ways of managers are past all explanation, and what’s the use of trying to fathom their ideas?

Loftus’s presence in Washington could hint at why Waldron left. Loftus took over for Jim Manning, who served as both manager and co-owner for Washington in 1901 before selling his controlling shares in the team. The New York Times noted on October 30, 1901 that while several stockholders lobbied Manning to retain control, he sold because of his strained relationship with notoriously imperious American League president Ban Johnson. Instead, Manning and future Hall of Famer Kid Nichols, who anchored the Boston Beaneaters pitching staff in 1901 got joint control of a Western League team, the Kansas City Blue Stockings, with Nichols to serve as manager. In January 1902, Nichols signed a number of players including, on January 19, Waldron.

I mentioned Waldron and Manning’s simultaneous move from Washington to Kansas City to baseball historian David Nemec, who wrote much of the text in The Ultimate Baseball Book. Nemec replied:

I checked my notes after we talked. They confirm everything you found and more. Manning was very popular with many players he managed and Nichols was still at the top of his game. He hated it in Boston and went to KC as part-owner. Although salary figures are unavailable, I suspect Waldron made more in 02 than he did in 01 with Washington. After Nichols left KC to come back to the majors, Waldron left too and went to SF in the fledgling PCL. Probably he followed the money; the PCL even then paid fairly well. Waldron I suspect was a lesser version of Willie Keeler, good contact hitter but one that didn’t walk much despite the small strike zone he presented.

I’ve mentioned before here– and I’m not the first person to say it– that generations ago in baseball, effective players with a glaring flaw or two like Waldron could often earn more in the minors than the majors, with the added bonus of being able to play in western states the majors didn’t extend to before 1958. Indeed, as a longtime reader pointed out to me when I emailed him about it, most of Waldron’s minor league career after 1901 is a series of sojourns through places like San Francisco, Denver and Lincoln, Nebraska.

There’s one other thing worth noting. Early in the 1902 season, with Waldron on his way to hitting .322 for Kansas City, he got an offer to jump to the Louisville Colonels of the American Assocation. George Tebeau who’d managed the previous Western League team in Kansas City in 1901 offered Waldron $350 a month, not far off of the National League maximum annual salary of $2,400. Waldron turned Tebeau down, giving his telegram to Nichols to keep as a memento. In an article on the incident in the April 30, 1902 Topeka Daily Capital, Nichols laughed, “Tebeau has always been anxious to sign Waldron. He was after him in the East at the time that I landed him.”

There may never be a definitive answer to why Waldron didn’t play in the majors after 1901. Short of tracking down one of his descendants through ancestry.com, which I don’t yet have access to, I’m not sure the historical record exists. But one thing is clear– for many years after 1901, Waldron remained in demand as a baseball player.