Regular readers may have noticed two changes in the last several weeks here: I have begun consistently posting Monday through Friday, and a fellow Society for American Baseball Research member Joe Guzzardi has contributed a Wednesday guest post. Joe recently offered to provide Saturday content as well, for the duration of the baseball season. Effective immediately, I’m pleased to offer this new bonus day of content. Joe’s Saturday column, “Double the fun,” looks at famous doubleheaders.

_________________

In recent blogs, I’ve written about Vern Law’s titanic 18-inning starting effort, Tom Cheney’s 16-inning, 21-strikeout masterpiece, and a tribute to the long lost doubleheader.

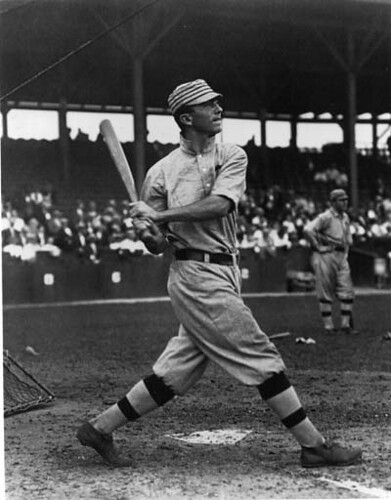

Graham Womack, in his regular Tuesday feature, Does he belong in the Hall of Fame? chronicled the great career of Brooklyn Dodger hurler Don Newcombe.

Today, I’ll roll marathon pitching, doubleheaders and Newcombe into a single post.

On September 6 1950 in a twin bill against the Philadelphia Phillies, Newcombe started both ends. That season the Dodgers played erratically and by early September, the team trailed the Phillies by 7-1/2 games.

Although the Dodgers had the Boys of Summer line up led by Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Gil Hodges and Duke Snider, pitching was thin, to put it kindly.

Newcombe and Preacher Roe, both with 19-11 records anchored the staff. Behind them were a pot luck group that included Carl Erskine (7-6), Erv Palica (13-8), Dan Bankhead (9-4) and Bud Podlielan (5-4). Their marginal success came thanks to heavy Dodger hitting rather than pitching skill.

With the season winding down, Newk was one of the few pitchers manager Burt Shutton could count on so he tapped him to start the first game. The Phillies countered with rookie righthander Bubba Church who took to the mound with an 8-2 record.

According to the Sporting News, Newcombe and Dodger manager Burt Shotton had talked on the train to Philadelphia about the prospect of his pitching both ends.

Reporter Joe King wrote that Shotton told Newcombe, “You can do two if you pitch a shutout in the opener.” Since Newk blanked the Phillies 2-0 on three hits in an efficient 2 hours 15 minutes, he got the nod to take the mound again in the second tilt.

“I figured he was hot right then and ought to try again,” Shotton said.

As the second game warm ups began, fans noticed that Newk was down in the bullpen taking his tosses. Realizing that something special was about to begin, the capacity crowd of 32,379 gave the Dodger stalwart a loud ovation.

Newcombe pitched valiantly allowing just two runs over seven innings but left the game trailing Phillie ace Curt Simmons, 2-0. Shotton then pulled Newcombe for a pinch hitter, even though he was one of the baseball’s best hitting pitcher. The Dodgers eventually rallied for three runs in the bottom of the ninth to win, 3-2.

Newcombe’s pitching line for the day: 16 IP, H 11, ER 2, BB 2, SO 3

The Giants and the Cardinals shelled Newcombe (13 IP; 10 ER) in his next two starts. Yet the Dodgers, inspired by Newcombe’s heroic effort, played top notch baseball for the rest of the season but ultimately fell two games short.

The Dodgers wrapped up its season against the Phillies with Newcombe absorbing the loss against Robin Roberts (20-11). That game brought down the curtain on majority owner/team president Branch Rickey’s Dodger tenure. Walter O’Malley replaced Rickey and immediately fired Shotton. Chuck Dressen took over as the new Dodgers manager.

Under O’Malley and Dressen, the Dodgers won four of seven National League pennants and one World Series before leaving for Los Angeles.

Newcombe went on to become a three-time 20 game winner. In 1956, Newcombe won the Most Valuable Player award and became baseball’s first Cy Young Award recipient.

_________________

Joe Guzzardi is a Wednesday and Saturday contributor here and belongs to the Society for American Baseball Research, as well as the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America. Email him at guzzjoe@yahoo.com.